When you first dip your toes into the world of investing and finance, the terminology alone can feel like a barrier to entry. Words like “derivatives,” “securitization,” and “tranches” often float around in financial news, usually without much explanation. Of these, the concept of a “tranche” is fundamental to understanding how modern debt markets work. While the term gained notoriety during the 2008 financial crisis, tranches remain a vital and common tool in global finance today.

This article aims to demystify tranches. We will strip away the jargon and explore what they are, why they exist, and how they function in the real world.

What is a Tranche?

The word “tranche” comes from the French word for “slice” or “portion.” In the financial world, that is exactly what it represents: a slice of a larger pool of securities or debts.

Imagine a large pie. This pie isn’t made of apples or cherries, but of thousands of individual loans—mortgages, car loans, or credit card debt. Instead of selling the whole pie to one person, financial institutions slice it up. However, unlike a regular pie where every slice tastes the same, these financial slices are different. Some slices are safer but less tasty (lower return), while others are riskier but potentially more delicious (higher return).

When you buy a tranche, you are buying a specific slice of that financial pie. Your slice has specific rules about when you get paid and how much risk you take on compared to the people holding other slices.

The Core Concept: Securitization

To understand tranches, you first need to understand the process that creates them: securitization.

Banks lend money to people to buy houses (mortgages). In the past, a bank would keep that loan on its books for 30 years until it was paid off. This tied up the bank’s money. To free up cash so they could lend to more people, banks started bundling these loans together.

- Pooling: A financial institution gathers thousands of loans into a single “pool.”

- Structuring: This pool is then divided into different layers, or tranches.

- Selling: Investors buy securities backed by these specific tranches.

This transforms illiquid assets (individual loans that are hard to sell) into liquid securities (bonds that can be easily traded).

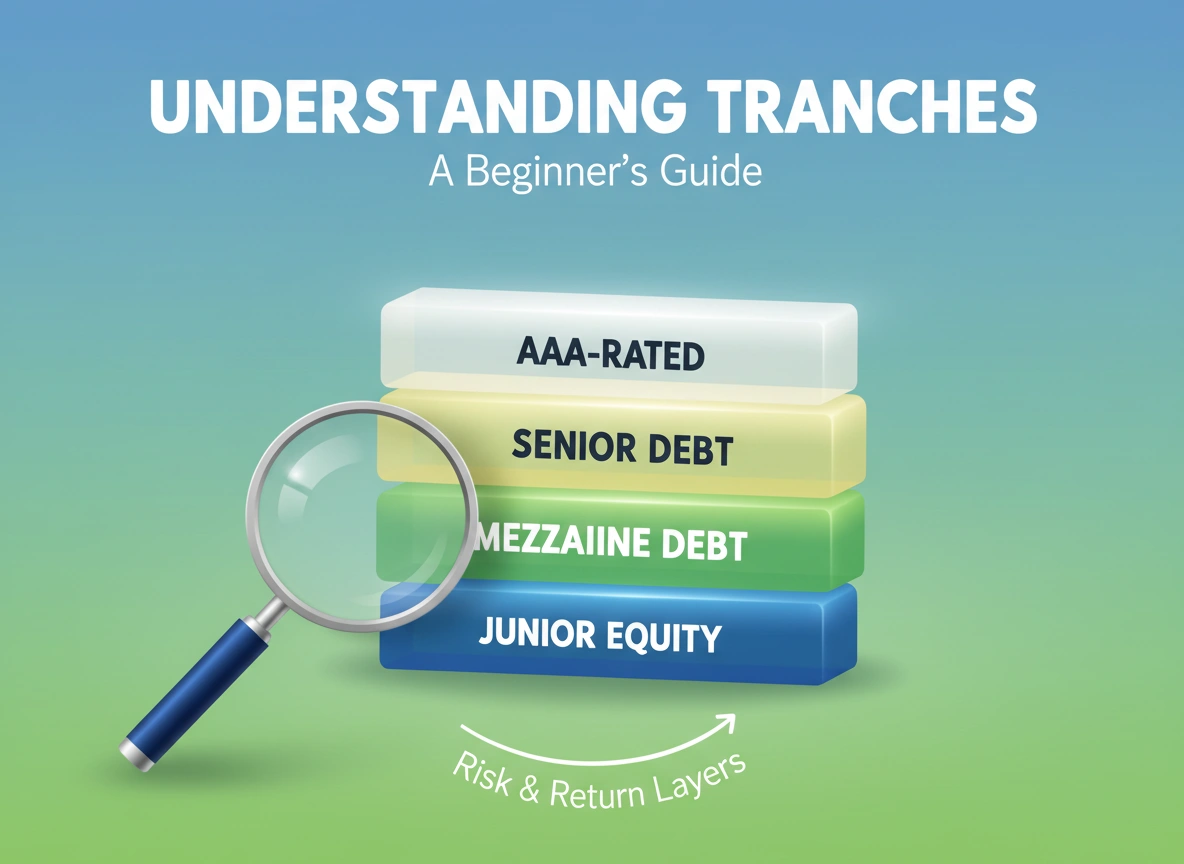

How Tranches Work: The Waterfall Structure

The most effective way to visualize how tranches work is the “cash flow waterfall.” Imagine a waterfall cascading down a series of buckets arranged vertically.

When the borrowers in the pool make their monthly loan payments, that money flows into the system like water.

1. Senior Tranches (The Top Bucket)

The money fills the top bucket first. This bucket represents the Senior Tranche. Investors who buy this slice get paid first. Because they have priority, their investment is the safest. Even if some borrowers stop paying their loans (default), there is usually enough money flowing in to fill this top bucket.

- Risk: Very Low

- Return: Lowest interest rate (yield)

- Credit Rating: Usually AAA or AA

2. Mezzanine Tranches (The Middle Buckets)

Once the Senior bucket is full and those investors are paid, the water spills over into the next buckets. These are the Mezzanine Tranches. These investors only get paid after the Senior investors are satisfied. If defaults rise significantly, the water might stop flowing before it fills these buckets completely.

- Risk: Moderate

- Return: Higher interest rate than Senior tranches

- Credit Rating: BBB to A

3. Junior or Equity Tranches (The Bottom Bucket)

Finally, any remaining water flows into the bottom bucket. This is the Junior Tranche, often called the “equity” or “toxic waste” tranche. These investors take the first hit if anything goes wrong. If even a few borrowers default, the water might never reach this bucket. However, if everyone pays their loans, these investors often reap the highest rewards because they bought the slice at a deep discount or with a high yield.

- Risk: Very High

- Return: Highest potential payout

- Credit Rating: Unrated or “Junk” status

Why Do We Need Tranches?

You might wonder why financial engineers complicate things by slicing up debt. Why not just sell the whole pool as one big bond? The answer lies in meeting different investor needs.

Customizing Risk and Reward

The financial market is full of diverse players with different goals:

- Pension Funds and Insurance Companies: They need safety. They cannot afford to lose their principal investment. They buy Senior Tranches because they want steady, reliable income, even if the returns are modest.

- Hedge Funds and Speculators: They want high returns and are willing to gamble. They buy Junior Tranches hoping the economy stays strong, allowing them to earn double-digit returns.

Tranching allows a single pool of debt to be sold to both conservative and aggressive investors simultaneously. It essentially creates a market for everyone.

Credit Enhancement

Tranching acts as a form of “credit enhancement.” By creating a Senior Tranche that is insulated from risk by the lower tranches, banks can create highly rated securities (AAA) out of a pool of loans that might only be average quality (BBB) on their own. The lower tranches act as a “loss absorption” shield for the upper tranches.

Real-World Examples

To solidify your understanding, let’s look at two common financial instruments that utilize tranches.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

This is the most famous example. An investment bank buys thousands of home loans from local banks. They pool them together into an MBS.

- The Senior Tranche might be bought by a retirement fund. They receive a 3% return, and as long as the vast majority of homeowners pay their mortgage, the fund is safe.

- The Junior Tranche might be bought by a sophisticated hedge fund. They might aim for a 12% return, but they know if the housing market dips and defaults rise by even 5%, they could lose their entire investment.

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

CDOs take the concept a step further. While an MBS is usually backed by mortgages, a CDO can be backed by a mix of assets—corporate loans, credit card debt, or even other mortgage-backed securities.

During the mid-2000s, banks created CDOs made up of the Mezzanine tranches of other mortgage securities. This was essentially “re-tranching” already risky debt. When the housing market collapsed, the math stopped working. The defaults were so widespread that the waterfall dried up almost instantly, leaving not just the Junior tranches empty, but the Senior tranches of these complex CDOs dry as well.

The Risks Involved

While tranches are useful tools for distributing capital, they carry specific risks that beginners must understand.

Complexity Risk

Because these structures involve complex mathematical modeling, it can be difficult to know exactly what is inside the pool. If the underlying loans are bad (like the “subprime” mortgages of 2008), the safety of the Senior tranches can be an illusion.

Correlation Risk

Tranching assumes that not all borrowers will default at the same time. It relies on diversification. However, in a major economic crisis, “correlation” rises—meaning everyone starts struggling at once. If housing prices crash everywhere simultaneously, the protection offered by the lower tranches vanishes quickly.

Rating Agency Reliance

Investors often rely heavily on credit ratings (AAA, BBB, etc.) to judge the safety of a tranche. History has shown that these ratings are not infallible. An AAA rating on a structured product does not always mean it is as safe as a US Treasury bond.

Summary: Key Takeaways

Understanding tranches is about understanding how Wall Street manages and sells risk. It is a mechanism that turns a bundle of loans into a menu of investment options tailored to different appetites.

Here is a quick recap of the essential points:

- Definition: A tranche is a slice of a pooled collection of securities or debts.

- Hierarchy: Tranches are arranged by seniority. Senior tranches get paid first and are safest; Junior tranches get paid last and are riskiest.

- The Waterfall: Cash flows from borrowers cascade down from the top tranche to the bottom. Losses flow up from the bottom to the top.

- Purpose: Tranches allow issuers to appeal to different types of investors, from conservative pension funds to aggressive speculators.

- Risk: While they help distribute risk, they do not eliminate it. If the underlying assets perform poorly across the board, even senior tranches can suffer losses.

By grasping the concept of tranches, you gain a clearer lens through which to view the global bond market. You can see how money moves from a homeowner’s monthly check to a pension fund’s account, and you can better appreciate the complex machinery that keeps capital flowing in the modern economy.Please click here for more info.

You may also read: Top 10 Unique Dog Names to Strengthen Your Bond